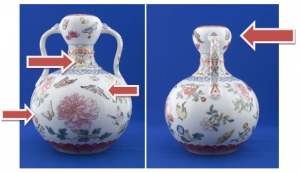

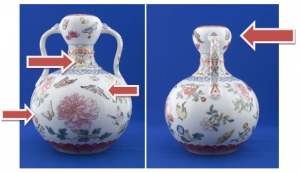

If presented with the Chinese vase pictured below, how should an appraiser with no specific knowledge of Chinese ceramics approach it to determine if it is fake or authentic? The best advice would be to “listen to the object.” But how does one “listen” to an object?

This may sound like a strange question, but the answers to it are critical to successfully appraising Chinese ceramics. As the famous Confucian proverb says: The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step. “Listening” is the first step on the journey of learning how to identify and value Chinese ceramics. As recent events in the news media have illustrated (such as the example of the $3 garage sale find in New York of a rare Northern Song dynasty [960-1127 AD] Ding ware bowl which sold at Sotheby’s in March of 2013 to the internationally renowned Asian art dealer Guiseppe Eskenazi for $2.2 million USD), a lot of money is at stake in being able to correctly identify Chinese ceramics. Considering the proliferation of high quality fakes in the market today, it is an area of appraising not for the faint of heart, but for those with excellent “listening” skills. If an appraiser “listens” closely enough, every object should reveal its true identity. This article will examine the most important strategies for identifying, dating and appraising Chinese ceramics, and then apply those strategies to demonstrate the reasons why the vase illustrated above, is in fact, a fake.

The most practical questions to ask when assessing a Chinese ceramic work of art are:

First: How does the object “feel”?

Most appraisers rely too much on visual assessment alone. The touch or feel of an object is a critical component which should be considered when determining age and authenticity. In this sense, appraisers should “listen” with both their eyes and their hands. There are two aspects an appraiser should use his/her tactile sense to evaluate: the weight of the object, and the glaze/painted decoration.

How heavy is it? When creating a fake, a copyist might look at a picture in a catalogue or online and thus would not know how the object should feel, the thickness of the body walls, and what it should weigh. This is one of the few aspects of an object which fakers often can’t get exactly right, because there is no substitute for holding a work of art. Especially in the days before easy international travel to auction previews, digital cameras and sophisticated computer software, the fakers often didn’t know the weight of a work of art, only rather what its physical appearance looked like from a very simple photograph. An appraiser needs to learn what different types of Chinese ceramics should typically weigh. Weight can also be affected by the clay it was made from, as well as the potter’s skill. The best way to learn what a piece “should” weigh is by holding other examples which are known to have a documented provenance, and so their dating can be trusted. The best venues to access correct pieces are in museums or at auction previews.

Appraisers must develop a memory bank of the sensations of holding various Chinese ceramics. This applies to not only getting a sense of the weight, but to the other important element which can be felt, which is the glaze itself and overglaze decoration.

Appraisers need to be feeling for whether the overglaze decoration has been chipped; if the glaze is glossy or pitted; and surface wear. Appraisers should also be aware of the various possible methods used to fake age, such as “immersing objects in acid, refiring them at a low temperature, and adding fake staple repairs, amongst others.” (1) As noted in the New York Times article, “A Culture of Bidding: Forging An Art Market in China” of October 2013, there are serious issues plaguing the current market in Chinese ceramics, including methods of faking used in Jingdezhen by craftsmen who even go to such lengths as “to build the wood-fired kilns that help create the subtle textures and glazes.”(2) Traditional methods of ceramic producation are used to try to create a correct glaze for the appropriate period.

Second: What is the shape of the object?

There is an excellent Beginner Guide to Chinese Porcelain Vase Shapes that can be found on www.Artnet.com. Helen Bu astutely notes that, “…it’s not difficult to find out when a certain shape was first produced, and whether or not that shape was popular during a certain period, thus making shape one of the key factors in dating the porcelain.”(3) Thus, an appraiser should be asking: Is the glaze and/or painted decoration correct for the period the work is supposed to belong to? As an example, consider a monk’s cap ewer which this appraiser came upon a couple of years ago. It featured polychromatic painting inconsistent with the Ming dynasty when the piece was purportedly made. Known correct examples from museums of this particular monk’s cap ewer shape were decorated exclusively in monochromatic glazes. An appraiser should start by asking whether the shape existed in the time period it is supposed to belong to, and if the decoration is also suited to that period. Certain shapes only appeared at certain times. This is a basic starting point, but is often overlooked in the rush to decide on authenticity.

Third: What is the Provenance?

Due to the high number of Chinese ceramic fakes in the market, documented provenance is of paramount importance. The history of the ownership of a work of art, if it can be documented, can dramatically increase the value of a work of art. These days, fakers are so desperate to try to deceive potential buyers, that even auction/provenance labels from old sales of reputable auction houses are being faked.

All appraisers should be aware that, generally speaking, Certificates of Authenticity from Hong Kong, particularly from the 1980s, should not be regarded as reliable, or serve as evidence of provenance. Another helpful point with regard to dating and provenance is that the red wax seals sometimes seen on the base of a piece, usually indicate that the item was brought out of the People’s Republic of China, sometime after 1954, and most likely after 1972 to the US (or in the case of Canada, post 1970). Jan–Erik Nilsson, on his website www.gotheborg.com discusses export approval seals (or jianding as they are known in Chinese) (4). An appraiser must remember that true cultural antiques (prior to 1795) cannot be legally removed from the People’s Republic of China. Anything considered antique, typically 100 years old or more, needs to been inspected by the Chinese Cultural Relics Bureau, and if deemed not of cultural importance, will be affixed with a red wax customs seal to indicate that it can be exported from the country. Most of the seals can be found on post-1900 pieces. (See endnote 4 for more specific information about styles of seals and the dating of red wax seals.) Appraisers should study pieces with a solid provenance found in the best collections in the world of Asian ceramics, including the Percival David Collection (5) now housed in the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum (also in London, England), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Fourth: What can Reign Marks Tell Us?

There are numerous types of marks found on Chinese ceramics, from Imperial reign marks, place marks, potter’s marks, marks of good wishes, and date marks. Imperial reign marks are of significance to examine in further detail because these are the ones most often being faked. They are typically located on the base, but sometimes on the body or neck of an object. There are various styles, including the most commonly found: zhuan shu (archaic style) and kaishu (regular script). However, the reign mark should actually be one of the last factors in trying to determine authenticity because of the ease with which they are faked. Daphne Rosenzweig, PhD CAPP, in her article “Qianlong-His Mark Lives On,” states: “A problem at present in the field of Ming and Qing ceramics is that many workshops on the mainland (the Jingdezhen area in particular) are laser-copying on to new works marks from acknowledged genuine older works, then covering the newly-minted marks with a brand-new traditional-formula glaze. You cannot chip off the mark, as one can with the spurious orange-red overglaze enamel marks found on so many ‘style of 19th century’ works. It is a ‘genuine’ mark, just not original to the piece. Deception is common, and detection is difficult.”(6)

When the mark can be identified as not correct to the period, it is referred to as apocryphal. The most accurate way of describing a piece which is genuine is to state, as an example, “With Qianlong mark and of the period.” Although marks can be in red or blue, other important factors in determining authenticity include the appearance/shade of the cobalt blue used in ceramic production which has changed over the centuries depending on where the cobalt was geographically acquired. There is also a theory called the “hollow-line” which advances that the authenticity of the mark can be determined from the way in which the calligraphic strokes of the Chinese characters are written.(7)

Since reign marks cannot be relied upon, the question of thermoluminscent (TL) testing often comes up, as a way of hopefully definitively dating an object. In the recent past, TL testing was popular as an authentication tool. Now, however, because of clever fakes and other drawbacks in the process, this is a less common option to pursue. Appraisers must still rely on their visual and tactile skills. Clever fakers have been known to combine parts of ceramics from various pieces to create one whole object. Thus, for example, in the case of a Tang Horse, the accuracy of the results could be altered by the location on the object from where the sample is taken (an old part or a new part of the overall piece). It is also a test which is not recommended for finer porcelain objects due to the damage which sample taking can cause. Another consideration is the fact that fakers can acquire “old” clay from the same geographical areas as potters did hundreds of years ago, and this can also present challenges in obtaining accurate test results.

Fifth: What is happening in the current art market for Chinese ceramics?

An appraiser should be familiar with the current art market for Chinese ceramics, which is filled with fakes. Regarding the use of the term ‘fake,’ it is generally considered to be defined by the intent of the artist/potter to deliberately deceive, whether this label is used. It needs to be acknowledged that the Chinese have a long tradition of copying, in other words, reproducing works of art as a respectful homage to tradition and previous great artists. Today, however, the reality is that the intent of the potter is often to deceive potential buyers and serious efforts are made to do so.

Millions of Chinese ceramics are produced on an annual basis in Mainland China. Some of the best fakes are being made in Jingdezhen, the traditional Chinese porcelain capital for more than a thousand years. Consumer demand from the nouveau riche has led to the proliferation of fakes in the market because collecting Imperial porcelains has become an expression of cultural sophistication. Artists are trained to produce fakes, and they excel at their work. Combined with technological advances, high quality fakes are becoming the norm, not the exception. There is an excellent BlogSpot by Peter Combs, www.plcombs.blogspot.com on which you can find articles such as, “Ten Things You Must Know about Collecting Chinese Porcelain.”(8) Combs goes into great depth discussing issues and strategies which can be utilized to learn how to tell real pieces from fakes. One of his points which should be stressed but is often overlooked is the fact that, “high prices do not indicate authenticity.”(9) Combs also shares his opinion on fakes on eBay and other Internet websites. While noting there are possibly some good Chinese ceramics being sold on eBay in the US, he states that an appraiser should realize that, “Any antique Chinese porcelain purporting to be Imperial, Ming, Song, Tang, Yuan or older than 120 years that is being sold on EBay USA from a location in China, has a 99.9% chance of being a total fake.”(10)

There is even the extreme situation of an entire museum in China being filled with more than 40,000 fakes! (11) It is now closed, but this reflects a phenomenon amongst wealthy Mainland Chinese buyers who are driving the market to new levels of record-breaking prices, and who not only collect what they believe to be authentic ceramics, but are building their own museums to house their personal collections.

As is well-described in Lydia Thompson’s article, “The Path of the Chinese Art Market: Sustainable Growth of Bust”, from the 2012 edition of The Journal of Appraisal Studies (Edited by Todd Sigety), confidence in the market is being undermined by price manipulation, bribery, and the non-payment issues, particularly at auction houses in Mainland China. (12) One consequence of these issues is the fact that appraisers can be mislead when false sales are posted on databases. Therefore, appraisers must be cautioned to use only data from auction houses with which they are familiar and can verify the results.

Appraisers should keep abreast of developments in the market because it is important to know what is currently being faked. For example, the area of Republican period porcelains (1912-1949), which was traditionally considered less desirable and overlooked as far as collecting, has suddenly become more valuable in the current market. Since true Qianlong pieces are hard to find, and sell for extremely high prices, some collectors are shifting to the Republican period, and consequently, fake Republican pieces are starting to turn up. Song ceramics is another growing area of collecting these days, and so appraisers should expect to see more fakes in the market for earlier ceramics as well.

Case Example of a Fake:

The strategies just outlined above regarding weight/feel, shape, provenance, reign mark and the current market will be used to explain this appraiser’s conclusion with regard to the case example being a fake:

The story of this vase begins in 2006. A fellow appraiser believed it was an example of a ‘mark and period Qianlong’ vase, with a potential value of $1-1.5 million USD (a high amount even at that time before the market exploded as it has done over the past five years). The opinion of the author of this article was solicited from a photo, but as all appraisers know, it is best to examine works of art in person. Even before holding the vase, this appraiser noted there was something not quite “right” visually about it. The strategies involved in “listening” to the vase were then applied with the following results:

1) Feel: When held, the vase was considered heavier than most other typical Qing dynasty porcelain examples from the appraiser’s past experience. (See arrows on the front and side illustrations of the vase above.) Notably, the unglazed/ground portion of the mouth rim should not have been ground down. The roughness could be felt with the fingers, and dirt seen with the eyes. An appraiser should also ask, is the wear correct? The glaze, in this appraiser’s opinion, seemed too shiny and new.

2) Shape: Is the form correct? In this example, it is a suantouping ‘garlic-mouth’ vase; or ‘garlic-head-shaped’ vase. This type of vase has been made since the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), and in the Qianlong period (1736-1785) of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). However, in this appraiser’s opinion, the globular lower body seemed rather heavy and the garlic-head and neck thicker than is ideal. The body should be typically pear-shaped, with a slender neck.

3) Provenance: The story which came along with this vase from the consigner was that the current owner’s father had fought during World War II in East Asia, and had brought it back to Canada after the war. Personal accounts of objects cannot be taken at face value. Stories have a tendency to be embellished or facts confused as information is transmitted between generations of family members. While it could very well be true that the vase was brought back in the late 1940s, and that would increase the chances of the vase possibly being of the Qianlong period, it certainly doesn’t imply or guarantee this fact.

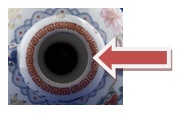

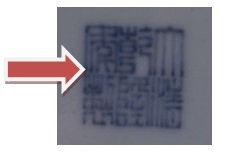

4) Reign Mark:

Examining the base of the piece reveals a six character Qianlong mark in blue in the archaic style. This reign mark reads, “Made in the Reign of the Qianlong Emperor.” It is ‘passable’ as being correct, however, upon close inspection, one could argue that the strokes of the last two characters on the left in particular, are not as well-executed as other examples when compared to verifiable Qianlong pieces. There is also pooling of the blue pigment in areas of the strokes which does not look as refined as it should to meet the standards of an Imperial piece. A detailed study could be made interpreting each of these factors (cobalt pigment and stroke execution) in the argument for or against the authenticity of this mark.

5) Current Market: Keeping in mind that antiques made prior to 1911 cannot be legally exported from China, and that authentic Qing pieces are actually quite rare, one should be asking then, how can so many be turning up regularly at auction houses all over the world? Perhaps the answer, sadly, is that fakes are being sold as authentic even in some auction houses, due to incorrect identification. The fact there is a dearth of Imperial pieces, in tandem with a growing number of wealthy buyers desiring to acquire such pieces, creates the perfect environment for fakes to flourish. Whether it is wishful thinking on the part of buyers, or deliberate deception by sellers, a market has been created which is setting record-breaking prices for Imperial pieces.

There are several further points regarding the painted decoration on the vase which add to the successful argument that this particular vase is a fake. This appraiser believes that the vase was copied from a flat two-dimensional photo, leading to distorted painted decoration on the vase. The manner in which the butterflies are depicted in particular, seem to be flat and stretched. The way in which they are outlined in black as well has a stencil-like quality. In addition, the lappet border of red lotus at the base is ‘heavy’; the ruyi (symbol of a stylized sceptre) at the top of the handles were not well defined; and the irises in particular seem spread out rather than compact around the lower floral band of the neck.

Conclusion: The mindset of an appraiser approaching the daunting task of authenticating Chinese ceramics must be open and realistic, rather like a detective investigating a mystery with no preconceptions or biases. The facts/clues must be “heard” by “listening” to them carefully. Having said that, it must be acknowledged that even amongst Chinese ceramics experts, there can be many varying opinions of age and identity by different experts even for the same object. In some controversial cases, a consensus cannot be reached. Due to the financial and legal implications of the difference between a fake Qianlong vase (a few hundred dollars for a decorative value) versus several million dollars for a ‘mark and period’ piece, appraisers will notice in auction catalogues the use of words such as “probably” or “possibly” to qualify the degree of certainty in the authenticity of an object.

One last piece of advice: All appraisers should build their own database of fakes to keep on file. In fact, in the long run, it could very well be more useful to keep photos and records about the fakes than originals. This data can be used to compare when appraising questionable works of art. Appraisers in major cities should also frequent their local Chinatowns to see what ceramics are currently filling the shelves.

The strategy of letting the object “tell” you what it is through objective observation with your eyes and tactile examination with your hands, should reveal its true identity. All of these factors, considered together, contributed to the conclusion that this particular example of a ‘Qianlong’ Chinese vase is fake.

Endnotes

(1) There is a website: www.chinese–antique-porcelain.com/porcelain-age-faking, which outlines the possible creative methods used to fake age on Chinese porcelain

(2) By David Barboza, Graham Bowley, and Amanda Cox, “A Culture of Bidding: Forging an Art Market in China,” New York Times, October 28, 2013.

(3) Helen Bu. Search www.artnet.com/insights/art-education/beginners-guide-to Chinese-porcelain-vase-shapes. She provides a chronological history of the rise in popularity of certain shapes from the Song dynasty to the present.

(4) Red wax seals are an area for which this author could find very little academic information. Generally speaking, most wax seals appear post-1954. There are basically four types: 1) the hexagonal in the circle; 2) the hexagonal only; 3) the circle only; and 4) the circle with no Chinese. They date roughly from 1954, 1964, 1980s, and post-1980s respectively. Further academic research in this area would be of interest to scholars and appraisers. Erik Nilsson notes on his website that there are three main cities in which the Cultural Relics Bureau operated, at various times: Guangdong, Tianjin and Zhejiang.

(5) The Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art is a collection of approximately 1,700 pieces of Chinese ceramics from the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, including the famous pair of Yuan-dynasty dated vases. The collection dates back to 1927 and 1930 when Sir Percival travelled to China and acquired pieces (often through palace eunuchs and government officials) originally part of the Imperial collection at the Forbidden City in Beijing. It is now on permanent public display in the British Museum, London, England.

(6) Daphne Lange Rosenzweig, PhD, ISA CAPP wrote an excellent article “Qianlong- His Mark Lives On”, for the Journal of Appraisal Studies, (ed. Todd Sigety), 2011 edition, pp. 255-263.

(7) www.gotheborg.com, has more information and illustrations demonstrating the different types of stroke executions, comparing solid and hollow. In 1978 Calvin Chou originated this idea that dating could be determined by this analysis, with a “hollow-line” implying a later date.

(8) (9) & (10) www.plcombs.blogspot.ca“What’s Fake and What’s Real Antique Chinese Porcelain?” He also has a website: www.plcombs.com

(11) Wang Zonquan was the owner of the Jibaozhai Museum was located in Jizhou, northern China. Read the report in the www.telegraphy.co.uk October 28, 2013, by Tom Philips, who notes that there were examples of ceramics, “claimed [to be] more than 4,000 years old when the pieces in question were inscribed with simplified Chinese characters that only came into widespread use last century.”

(12) Lydia Thompson’s article on the many serious issues facing the Chinese art market, for the Journal of Appraisal Studies, (ed. Todd Sigety), titled “The Path of the Chinese Art Market: Sustainable Growth or Bust,” 2012 edition, (pp.159-167) should be read in its entirety by generalist appraisers.

Recommended books and websites:

There are several museums which have excellent comprehensive online databases of their collections, including the British Museum, the Victoria & Albert Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Appraisers should study their websites in order to find authentic originals with good provenance to use as comparison for evaluating other examples. The library of anyone seriously interested in researching and/or appraising Chinese ceramics should include, at a minimum:

- Davison, Gerald. Marks on Chinese Ceramics, 1994

- Hobson, R.L. The Wares of the Ming Dynasty, 1962.

- Kerr, Rose. Chinese Ceramics: Porcelain of the Qing Dynasty. V & A Publication, London, 1986, Masterpieces from the V & A collection.

- Medley, Margaret. The Chinese Potter: A Practical History of Chinese Ceramics. Phaidon, Oxford, 1976.

- Medley, Margaret. Ming Polychrome Wares, 1978.

- Medley, Margaret. Ming and Ching Monochrome, 1973.

- Medley, Margaret. Celadon Wares, second edition, 1998.

- Pierson, Stacy. Earth, Fire and Water: Chinese Ceramic Technology: A Handbook for Non-Specialists. 1996.

- Pierson, Stacy. Song Ceramics: Objects of Admiration, 2003.

- Scott, Rosemary. Imperial Taste: Chinese Ceramics from the Percival David Collection, 1989.

- Scott, Rosemary, editor. The Porcelains of Jingdezhen. Colloquies on Art & Archaeology in Asia, No.16, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, 1993.

- Scott, Rosemary. For the Imperial Court: Qing Porcelain, 1997.

- Vainker, Shelagh. Chinese Pottery and Porcelain- From Prehistory to the Present. British Museum Press, 1991.

- Gotheborg.com by Jan-Erik Nilsson, “Ten Rules on How to Deal with Fakes” https://www.gotheborg.com/glossary/index.shtml

- For an enjoyable fictional account of the experience of authenticating Chinese ceramics, Nicole Mones’ A Cup of Light, 2003, makes for a good read, and is based on historical fact.

About the Author

Susan Lahey, MA, ISA AM, is a qualified personal property appraiser (USPAP & ISA), specializing in the fine and decorative arts of Asia, with a focus on Chinese art. She speaks Mandarin and reads traditional Chinese, and provides appraising, lecturing, teaching, and consulting services. Ms. Lahey is a graduate of the University of Toronto (BA) and the University of British Columbia (MA), as well as the Sotheby’s/SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, England) post-graduate diploma program in Asian art (China, India, and the Islamic World). Having a life-long fascination and admiration for Chinese culture and its arts, Susan lived in Taipei, Taiwan for two years, and studied at Stanford’s Inter-University Program for Chinese Language Studies at the National Taiwan University. She has also held various capacities at the Royal Ontario Museum. Most recently, Ms. Lahey served as the Department Head of Asian Arts at a Toronto auction house for six years, before establishing her own company Eastern Art Consultants Inc. in 2010, which specializes in the valuation of the fine and decorative arts of China, Japan, Korea, India, Southeast Asia and the Near East.

Contact:

Susan Lahey, MA, ISA AM

President, Eastern Art Consultants Inc.

Telephone: 647-283-8984

Email: easternartconsultants@gmail.com

Website: www.easternartconsultants.com